“We’ve been spending most our lives / living in a wombat paradise” — Anonymous

A common wombat (Vombatus ursinus) feeds on the open grasslands of beautiful Maria Island.

Just the photos: Autumn in Tasmania, 2024 Gallery

In the beginning, there was Brisbane… a conference in Brisbane in March 2024, which needed a healthy trip tacked on to balance out the nearly 48 hours of travel. I visited Australia once as a kid, but my principle memory is of picking leeches off after a hike. Sadly, not very usable information for planning. Australian wildlife is diverse and very widespread. Rainforest in the northeast, long coastlines, grasslands, and desert in the west… I struggled to narrow the scope, right up until the salient Google search… “Where is the best place to see wombats in the wild?”

Not to spoil the surprise… but it’s Tasmania.

Tasmania is an island state of Australia, located due south of the state of Victoria on the mainland. As soon as the idea formed to go there, I felt to my core it was perfect. As a mountainous, temperate island, home to a variety of unusual species (somewhat protected from more potent introduced species on the mainland), it has some notable similarities to some other excellent places. It has large areas of protected wilderness, and a lot of hiking. And Australia automatically recognizes any driver’s license issued in English! This trip was cobbled together from vague scraps of information, misinterpreting national park guidelines, and Google maps. It surpassed all expectations.

Dove Lake boatshed (1940) at sunset. I have never photographed so many charming little old buildings, but Tasmania is full of them.

Brisbane

A laughing kookaburra, the familiar and charismatic kingfisher of eastern Australia, perches in a patch of urban forest.

A dusky moorhen chick with enormous feet can almost walk on water… using lily pads to keep afloat.

We spent a week in Brisbane for the aforementioned conference prior to leaving for Tasmania. Photography was not a very high priority, but a few pockets of forest yielded some very habituated wildlife. All of these photos were taken with a 200mm lens. Tourist-birding can be delightful, as even the most mundane local species can be completely new and interesting.

Assorted wildlife of Brisbane. Taking the place of more familiar city birds, the Australian ibis is a seasoned city slicker, found all over city parks but also in vastly more urban areas… such as the Queen St mall in the CBD. Australian brush-turkey and Australian water dragon are almost as enterprising. In greener pockets of the city live such denizens as laughing kookaburra; little pied cormorant; Australian magpie; bush stone-curlew (so unbelievably still you could miss them standing right in front of you!), dusky moorhen; and gray butcherbird. Black flying-fox roost along the rivers and make an unbelievable amount of noise: you can’t miss them if they’re around.

Bruny Island

Portrait of a tawny frogmouth after dark on South Bruny. Though frogmouths present a rather owl-like appearance, with their huge eyes and flatter faces, they are more closely related to nightjars… and even hummingbirds.

Our first stop after our plane to Tasmania touched down was a pie shop in Hobart. Our second stop was the tiny ferry to Bruny Island, off to the southeast. We spent our first couple days birding around the island with the help of a guide from Inala, a private reserve established to protect a population of endangered forty-spotted pardalotes.

Left: Tasmania’s least colorful robin is also its only species endemic: the mouse-gray dusky robin. This individual was foraging in the low bushes near a campground at South Bruny National Park. Right: Boldly marked New Holland honeyeaters are found throughout southern Australia, but this one perched helpfully right off the path to the Cape Bruny lighthouse.

Bruny is home to all 12 of Tasmania’s endemic bird species:

- Tasmanian nativehen (Gallinula mortierii)

- Green rosella (Platycercus caledonicus)

- Dusky robin (Melanodryas vittata)

- Tasmanian thornbill (Acanthiza ewingii)

- Scrubtit (Acanthornis magnus)

- Tasmanian scrubwren (Sericornis humilis)

- Yellow wattlebird (Anthochaera paradoxa)

- Yellow-throated honeyeater (Lichenostomus flavicollis)

- Black-headed honeyeater (Melithreptus affinus)

- Strong-billed honeyeater (Melithreptus validirostris)

- Black currawong (Strepera fuliginosa)

- Forty-spotted pardalote (Pardalotus quadragintus)

This was early autumn for Tasmania, past the breeding season for most species. Therefore, we missed the breeding-endemic swift parrot, and the fairy wrens were in their dull brown eclipse plumage. Nevertheless we spotted almost every endemic (at least from the perspective of the checklist, not the camera) in our abbreviated two days on South Bruny.

One of those flashy birds found on Tasmania, the scarlet robin. We saw more scarlets on this trip than any other robin, but I’m shallow so they got me every time.

In all honesty, my main targets were the brightly-colored robins (okay, and one dully-colored endemic robin)… In particular, the fantastic pink robin. But though we spent hours combing through ideal rainforest habitat, we never turned up a good look at the pink on Bruny. (Scarlet robins were prevalent in any patch of open forest.)

Our first night drive turned up a staggering number of brushtail possums and pademelons, and a few eastern quolls. The next night, we watched a tawny frogmouth pop out of the woods to hunt moths by the vehicle headlights.

On a nighttime quoll patrol, we turned up this eastern quoll feeding on roadkill. He was so preoccupied that he paid me no attention whatsoever as I crept behind the vehicle for this photo.

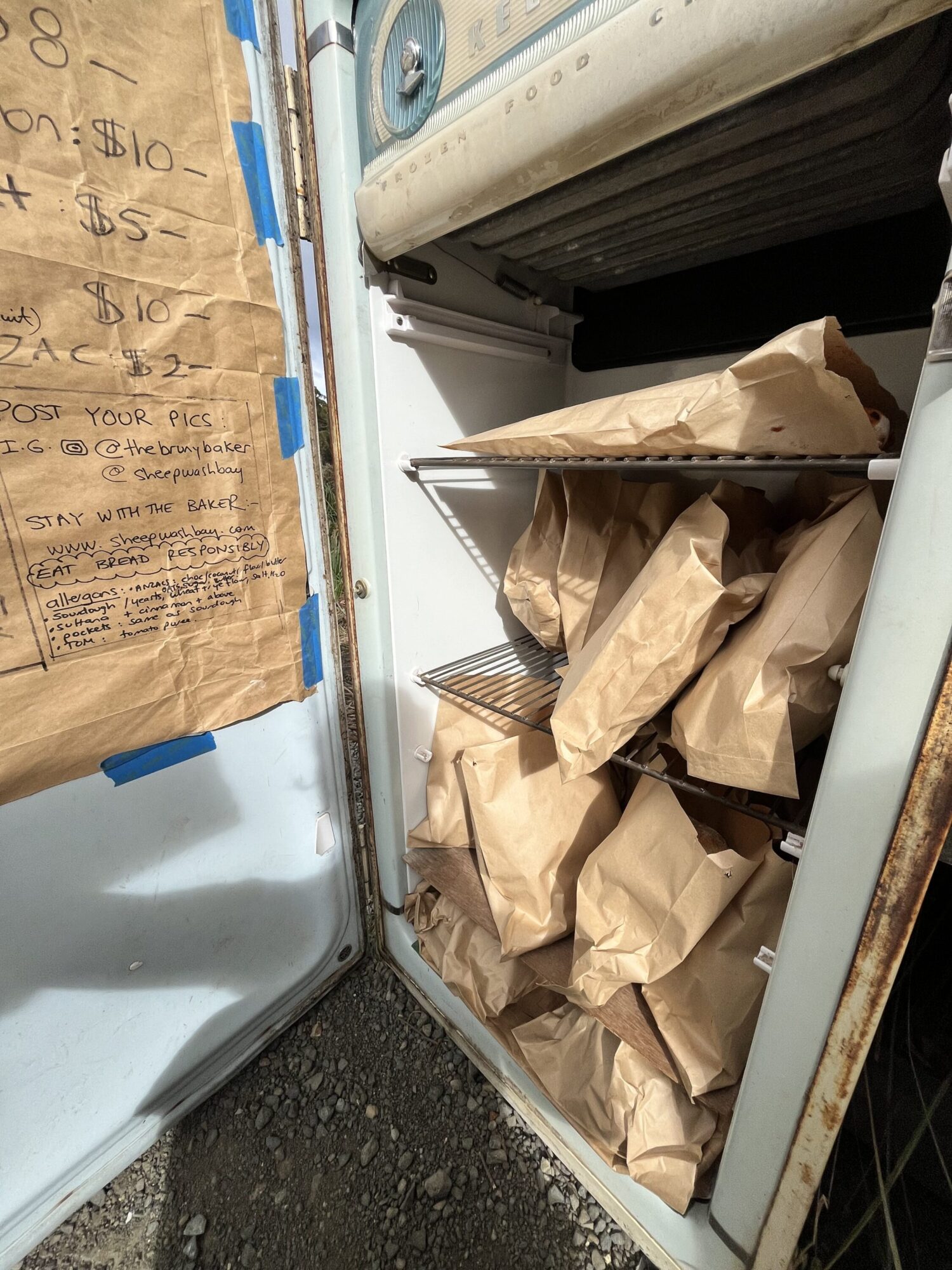

On our last morning on Bruny, we looked for white morph grey goshawks. And then we were off, to make our 15:15 ferry from Triabunna to Maria Island. But we checked the bread fridge first!

An adult forest raven displays in the rain. This is sort of an “almost-endemic” species, being restricted to Tasmania and small parts of mainland Victoria.

Maria Island

Long have I lived on this earth with no real direction towards seeing my first wild wombat… and now, enlightened, I know I wandered in darkness.

Maria Island is a small island off the east coast of Tasmania. While remnants of historical settlements remain, it is now entirely protected within Maria Island National Park. A ferry provides pedestrian access. Hiking or biking are the only ways to access further flung areas of the island. Bunk rooms are available in the historical penitentiary (for those desirous of some luxurious convict-style accommodation), and otherwise there are campgrounds.

We camped in Darlington for two nights. Initially we planned to bike-pack the full island, but our bike rental fell through (which may have been a blessing in disguise, who can say). It turns out, we were quite over-geared for the experience of camping at Darlington. I prepared for a normal backpacking experience, but between flush toilets, a picnic shelter with food lockers and gas grills, and water taps (non-potable), it was probably the most luxurious tent camping experience I’ve ever had. There are even massive trolleys available at the ferry dock to pull your gear to the campground. If inclined, one could probably pack one’s entire home kitchen along on the journey.

A wombat wanders through our campsite on Maria Island… or perhaps more accurately… her campsite.

Maria Island is undoubtedly the best place in the world to see wild wombats. While through much of their range they are mostly nocturnal, on Maria they can easily be seen foraging during daylight. The most productive time for us was late afternoon and evening (which necessitates a sleepover on the island). A number of them are vastly unconcerned by people. Several times (while tracking from a polite telephoto photography distance) I was surprised by a different wombat nearly foraging right into me. A few lucky wider angle photos were managed by waiting in place for a wombat to wander my direction. (It goes without saying, but even with mindbogglingly “tame” wildlife, maintain normal best practices to avoid disturbing their natural behavior.)

Maria is also a good place for Cape Barren geese and forester kangaroos. Nearly all of the Tasmanian endemic birds are found here. A facial tumor disease-free population of Tasmanian devils was also introduced to the island in 2012. They proved to be the doom of all of Maria’s little penguin colonies… conservation can be a zero sum game. We saw no penguins, and nothing of the devils either but very old scat.

Two views of the Ruby Hunt cottage, high on the hill overlooking Darlington Bay. Ruby Hunt was one of the last inhabitants of Maria Island, staying til 1968. She operated a pedal-powered wireless, which in the early half of the 20th century, was Maria’s only communication link to mainland Tasmania.

We landed on Maria around 4pm, and made the leisurely walk to select our campsite. On our first night, we set up in the overflow area, which overlooks a wide grassy hill. I chose our spot in part for solitude, and in larger part because I already saw a number of wombats foraging away on the rise. It was an arduous trek about 50 feet up the hill to begin our first official wombat viewing of the trip.

By the time we reached the picnic shelter to rehydrate our dinner, we were cooking by phone flashlight. A few southern brown bandicoots evidently consider the picnic shelter their domain. I hadn’t expected to see bandicoots at all, but these bandicoots were more than bold… They may have even been oblivious as they scampered around our feet (and sometimes over them), in search of crumbs.

Assorted shots from our first two days on Maria. Various landscape and other scenery, wombats of course, Cape Barren geese, Tasmanian pademelon, forester kangaroo joey in landscape, a red-necked wallaby (bigger than a pademelon, smaller than a kangaroo!) feeding, and of course, a southern brown bandicoot, one of our frequent meal companions.

The next morning, I wandered around the grounds at Darlington photographing Cape Barren geese, before hiking out to the airstrip to see if we could spot the mob of forester kangaroos known to forage there. These kangaroos are a Tasmanian endemic subspecies of the eastern grey, descended from agricultural “problem animals” released on Maria Island in the 1970s. The population did so well that it began to impact vegetative regrowth, and it is now managed. We spotted a large group spread out over the open hills, and watched them for a while (from a distance: the kangaroos are warier than the smaller wallabies and pademelons) before walking back to the picnic shelter to treat with bandicoots (i.e., make breakfast).

A large male forester kangaroo hops along a hill crest overlooking the bay in the mid-morning.

Though the marsupials on Maria are definitely unusually easy to see, we found that the wombats prefer a late breakfast. Midday, we opted for a hike to pass the time. Bishop and Clerk are a pair of towering dolerite cliffs on the shoulder of Mount Pedder. A ranger warned us that the cliffs were dangerous on windy days, and naturally, it was indeed a windy day. Nevertheless, we set out to see how far we got before it got too sketchy.

The track makes a short day hike: roughly 8 miles round-trip, with just over 2k feet of gain. The primary challenge is a short scramble at the top. At this point the strength of the gusting wind and the sheer drop combined their powers and gave me acrophobia. I anchored myself in a crevice and took the best pictures I could from that sad vantage… ha!

Views from the Bishop and Clerk track.

In the afternoon, we tracked more wombats. Many of them seem to prefer evenings to mornings, and start to appear around 3pm. Before then, the fields can be completely deserted of life, with only their bizarre, cuboid droppings left behind.

Right: A wombat joey races downhill, straight past me as he makes for his burrow. Left: His mother still forages up on the rise, apparently completely unconcerned.

I watched a wombat joey follow some fresh grass down towards the beach, losing his mother in the process. Usually joeys follow their mother closely, and rush to catch up when they realize they’ve been left behind. I expected him to burst up the hill after her at any time. When he didn’t appear after a long wait, I went to look for him. He was still blissfully grazing in the shade. Over the next half hour, he ambled about 20 feet, taking frequent snack breaks. I was downhill, having noticed cluster of burrow holes down near the beach. I was barely ready with my camera when he broke in to a sprint down the hill, missing me by only feet! (On other occasions, we noticed they tend to run, or at least amble quickly, towards burrows. At all other times they set a quite leisurely pace.)

Left: a female wombat strides across the field, her pouch so full it’s nearly dragging on the ground. One has to imagine that the joey inside will be walking for himself very soon. Right: A forester kangaroo joey near the edge of the eucalyptus woods.

The next morning I rose before dawn and walked through the sparse eucalyptus woods, spotting some shyer wombats and pademelons feeding in the darkness. Eventually I found myself down by the beach photographing shorebirds, before it was time to pack up our campsite and catch the morning ferry back to the mainland.

Hooded plovers, pied oystercatcher, Pacific gull, silver gull, white-fronted chat, a nonbreeding Caspian tern, little pied cormorant.

By the River Leven

A panorama over Jacob’s Ladder, the single land access road that climbs to the high plateau of Ben Lomond

We had a long drive once the ferry landed, from the southeast coast all the way to the northwest mountains. Our first stop at Ben Lomond National Park, the home of one of Tasmania’s only ski areas. It is high, steep-sided plateau of dramatic dolerite and alpine flora. I would have enjoyed seeing this area during winter operations, but alas, we didn’t have several months to wait for snow.

Lodges at Ben Lomond under dramatic cloud cover

Our route passed through Tasmania’s second largest city, Launceston, then through the agricultural Cradle Coast region. (Signs along the route declare it the “Tasting Trail.” For what it’s worth, a farm shop in Turner’s Beach does make the best strawberry crepe I’ve had in my life.) We finally ended the day in a quiet, isolated valley under the eye of Black Bluff.

A black currawong, a Tasmanian endemic. Though superficially similar to crows, they’re not closely related.

Mountain Valley is a private reserve, much like Inala. It protects over 100 acres of wet sclerophyll forest, old growth rainforest, and a fascinating system of caves. It’s a release site for rehabilitated wildlife (leading to some remarkably habituated individuals, like a scarred old pademelon who hopped along after me on a walk around the property), and often mentioned as one of the best places to see wild Tasmanian devils. We spent two nights here for that reason alone, but this quiet valley was one of the most peaceful, beautiful places we encountered on our tour. Sitting by the glass door of our cabin, watching mobs of fairy wrens hop across the mossy lawn in the early morning, is one of my favorite moments of the trip.

By night we saw brushtail possums all over Tasmania, but here we also heard them… pattering across the cabin roof in possum whirlwinds.

On to the devils. The populations on the Tasmanian mainland were heavily affected by devil facial tumor disease. Their noisy feeding frenzies may be a thing of the past. There are so few of them that individuals poke in and out of feeding opportunities quietly. They’re still very much in danger of becoming secondary roadkill from feeding on roadside carrion.

That night, sitting by the cabin door, we saw a nearly constant parade of pademelons and brushtail possums. (We learned that the Wikipedia entry for possums neglected to mention that they are voracious meat eaters… Those possums would give dogs a run for their money in sheer gluttony.) Past midnight, I was falling asleep on the floor, opening my eyes every minute or so to scan the yard. I had just resolved to finally go to bed when something appeared at the edge of the porch light…

A small Tasmanian devil that crept by our cabin past midnight, so quick and silent you could have missed it…

The next night, the first devil padded through almost moments after full dark. A Tasmanian boobook flew by about an hour later. And at around 22:00, an enormous devil with a scarred face passed through, sniffing cautiously after possum trail.

All nocturnal photographs are lit by dim continuous light which the animals can choose to avoid; not with flash. It was a thrill, and surreal, to watch these animals, so rarely seen at all, in the dead of night.

Though Tasmanian nativehens were extremely common everywhere we went, it was in Loongana that we learned they can swim. One evening, watching for platypus, we saw a parade of hens paddling through the river. All of a sudden they all started alarming in unison, a tremendous noise that cannot possibly be described. Turns out, they found our first platypus for us.

Cradle Mountain

Stars reflect in Dove Lake in Cradle Mountain National Park. An hour and change past sunset, the scene is completely dark to the eye, but the long exposure still picks up the last glow of sunset on the ridge.

A wombat (with plenty of wombattitude) at home in the buttongrass plains of Cradle Mountain.

Our last few days were spent in Cradle Mountain National Park, famous for incredible scenery, excellent hiking, and… wombats? We’d find out. We arrived in the afternoon and wrapped our heads around the shuttle schedule and park entrance rules. Then, I wandered out to walk some of the short trails that start near the lower ranger station.

A female pink robin, Pencil Pine Falls, and a Bassian thrush.

As I passed through a car park on my way between trails, I heard a familiar chip… chip… chip… from a small copse of thick brush, and puzzled over it for a moment. It struck me as distinctive, but I couldn’t believe my identification. I looked around the car park, the afternoon sun glaring off car windows. I peered into the brush. My eyes took a moment to adjust. I saw a small brown bird. I stared harder. I saw… a flash of bright pink.

My precious first pink robin… a denizen of the Cradle Mountain Interpretation Center parking lot.

It is truly a moment of classic birding irony that after multiple days spent combing through pristine, ideal pink robin habitat all the way across Tasmania, my first sighting of this notoriously elusive bird would be in a bush in a car park.

A red-necked wallaby enjoys a good belly scratch, which is relatable.

The night was clear, so we went up after the last shuttle to watch the stars rise over beautiful Dove Lake. I’m not a very nuanced stargazer, but somehow the southern sky feels different.

Cradle Mountain rises over calm Dove Lake. The Milky Way is visible to the left, though a bit dim so soon after sunset.

Reflections in perfectly still Wombat Pool.

The next morning, we caught the first shuttle into the park and got off at Ronny Creek. We hoped to spot our first Cradle Mountain wombats. We were thoroughly skunked that morning, but had a pleasant hike, passing over the boardwalk through misty buttongrass plains, up to the beautiful, still Wombat Pool (the signs for which have been defaced to read “Wombat Poo” instead… which is also true), Marion’s Lookout, and on to the foot of Cradle Mountain. The descent past Lake Wilks was steep, even scrambling in sections, before dropping to the gentle Dove Lake circuit. The extremes of the trail were pretty funny. The longest sections of flat boardwalk I have ever seen in my life, dropping off into incredibly steep, exposed scrambling in the blink of an eye… then back to boardwalk.

Spiders in the buttongrass, Wombat Pool, Dove Lake from Marion’s Lookout, “Kitchen Hut” below Cradle Mountain.

A tarn in the high meadow approaching Cradle Mountain

We returned to Ronny Creek later that afternoon for a second try at the wombats. Perhaps, like on Maria, these wombats were also later risers. Indeed, where before there were only droppings, there now were wombats scattered across the buttongrass plains. We wandered through the plains, watching them attend to their wombat business, until it was time to catch the last bus out of the park.

A platypus surfaces in a still pond at dusk.

It had become my habit to check still pools of water for the elusive platypus whenever possible. During our stay near the Leven Canyon, we had a split second dusk sighting of a platypus at Mountain Valley in the River Leven. Buoyed by that sighting, we made a day trip to the Tasmanian Arboretum in Eugenana, where we were thrilled to see no fewer than three different platypus hunting in Founder’s Lake in broad (harsh) daylight. But it was at Cradle Mountain, in an unassuming pond near the lodge, that we had our absolute best platypus sighting of the trip. A small platypus was swimming in the pond in early afternoon. When we checked back just before sunset, he was still busy at work. What a joy to watch this industrious little fellow hunting ’til well after dark.

On our final day, I walked through the rainforest at dawn, and found myself amidst the motherload of pink robins. Their calls seemed to sound from every tree around me… with not a single flash of pink in sight! I sat on the boardwalk and waited, and listened, and moved a bit, and waited, and listened… After long minutes, I finally began to see them, at least with more success than I had been. It’s mindbending how easily such an ostentatious bird can disappear.

Narawntapu, and home

We had an evening flight out of Launceston, and a whole day to get there. After breakfast, we made our way to the northern coast and Narawntapu National Park. Wandering across the sunny beach, coastal heathland, then through open grassland, we watched for birds and forester kangaroos. I narrowly avoided falling asleep in the shade of the lagoon bird hide.

Yellow-tailed black cockatoo; forester kangaroo; grey fantail; Tasmanian thornbill (an endemic); galah, or rose-breasted cockatoo.

We managed to stay awake, making it back into Launceston with plenty of time to catch our flight to Brisbane… Or, so we thought. We actually arrived five minutes too late for check in. Yikes. Our flight info was an hour off. Beware that agents might have incorrect timezone information for Tasmania! Disaster was averted in this case… we were able to fly into Melbourne instead with no significant changes otherwise.

Still, this would be too traumatic an end to this trip report, so instead I’ll leave you with this wombat.

And an extra tip for any noodle lovers currently planning their bucket list wombat safari! We acquired a bottle of gin flavored with native Tasmanian mountain pepper at a farm shop on the northwest coast. I prefer gin to vodka in “vodka” cream sauce, and this is the best gin for that yet!

[…] time went on, of course, the plan kept changing. I accidentally planned a trip to Tasmania right over the roadtrip period (and it was anchored by a conference, so we couldn’t move it). We […]